Last call for feedback on the breast cancer draft guidelines

The deadline for providing feedback to our breast cancer draft guidelines is fast approaching. Please submit your feedback by August 30th here. We want to thank everyone who has responded up until this point. Providing your feedback is the best way to help us ensure we have the best, most accurate guidelines possible.

By providing feedback, you will help ensure the final guidelines are clear and feasible for clinicians to use in practice. We commit to reviewing all responses. Find the draft recommendations here.

From the front lines

Primary care providers are uniquely positioned and skilled to have shared-decision making discussions with their patients. Tools to help by each age group are provided on the Task Force’s website. Many women 40-74 will choose to screen but some may not. All deserve to be informed about potential benefits and potential harms in order to make an informed decision. Both decisions to screen and not to screen are reasonable and should be respected.

We often hear about the benefits of “early detection” – we are told that if we can find cancer earlier, then there is less chance of death from breast cancer or less intensive therapies. It might be surprising but early detection is not necessarily an assurance of either of these.

Outcomes of harms include additional testing showing no cancer (imaging and/or biopsy) and overdiagnosis. Overdiagnosis means the biopsy-proven detection of a pre-cancer or cancer that would otherwise never have caused the individual any symptoms or problems over their lifetime. This occurs for older women and is well documented to also occur in younger women.

Screening from age 40-74 is a personal choice. In the context of a breast/women’s health or preventive care discussion, individuals should be informed they are eligible for screening if they would like it.

– Michelle Nadler, Medical Oncologist

Assistant Professor, Clinician in Quality & Innovation, University of Toronto

Clinical expert, Breast Cancer Working Group, Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (2023-2024)

Get the facts

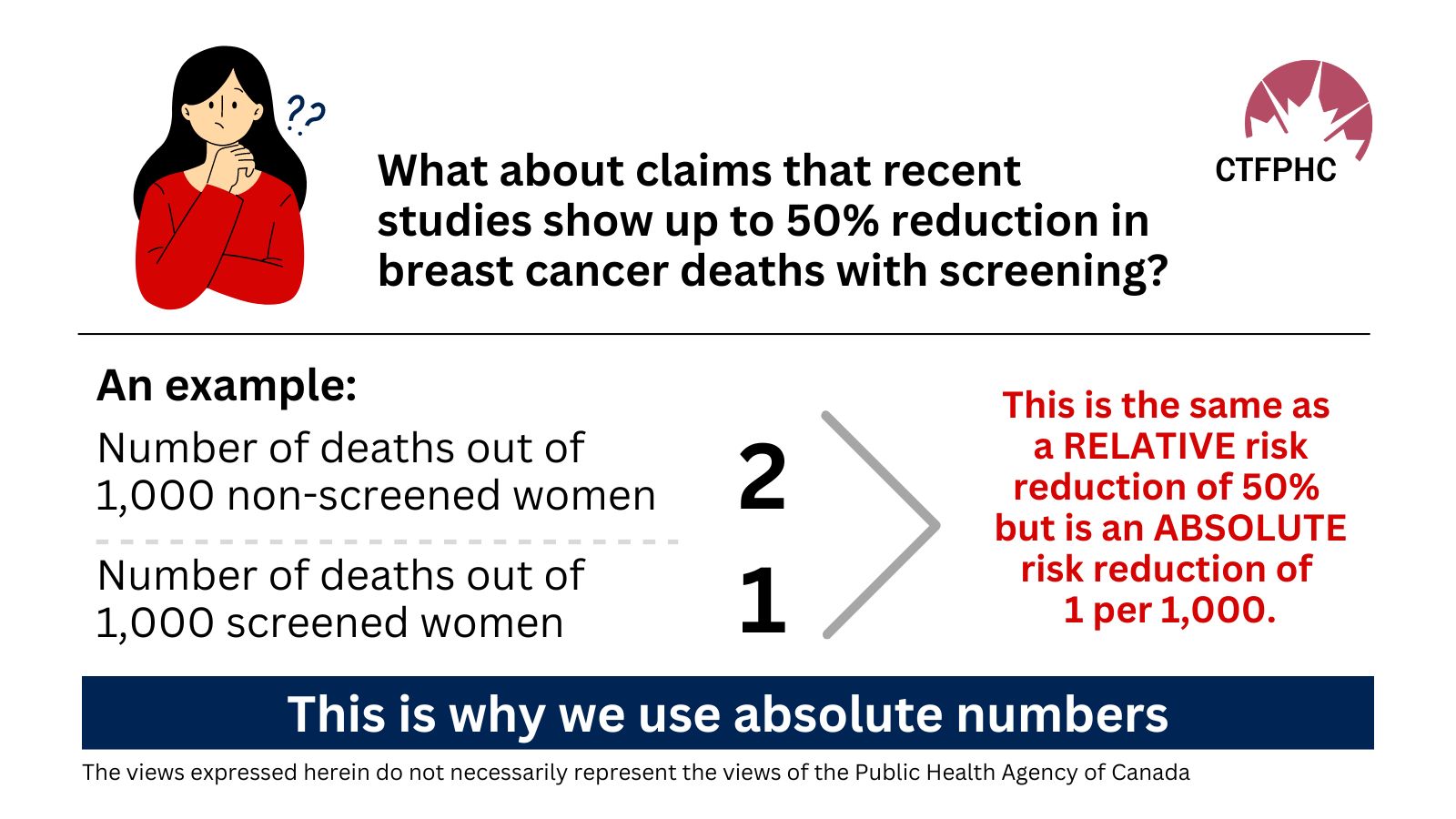

What is the difference between absolute and relative risk?

Risk is the chance of something happening and there are two ways to measure it – in absolute and relative terms. Statements on risk can be deceiving. It’s important to get the facts to have a full picture in order to decide how much risk you are willing to accept when undertaking a decision such as breast cancer screening.

Absolute risk is the actual risk of something happening, like the risk of a being injured in a car crash or risk of lung cancer among people who smoke.

Relative risk is a comparison between two groups of people – or in the same group of people – over time. It’s the change in risk (an increase or reduction) from the starting point of what you are measuring. For example, what is the relative risk of being injured in a car crash if I wear a seatbelt compared with not wearing a seatbelt, over 10 years? Or the risk of lung cancer among people who smoke compared with those who quit smoking, after 25 years.

Relative risk always seems larger and more dramatic than absolute risk and can be misleading. This is because it needs context to be properly understood as it can represent risk in a very small population. It is usually expressed in percentage increase or reduction. For example, I may get excited because I have increased my social media followers by 50% (relative increase). That seems like a lot. But if I only had 10 followers to start, it means I only have 5 more followers (absolute increase). On the other hand, if I had 10,000 followers to start, it would mean I have 5,000 more followers (absolute increase) which also seems like a lot.

To be as clear as possible, we use absolute risk in our guidelines. It is essential that the absolute risk, preferably in absolute numbers, is given in risk communication.

To learn more about the difference between relative and absolute risk, this is one example of a YouTube video that might be helpful from “Talking with Docs.”

What is overdiagnosis?

Surprisingly, not all cancers would have gone on to cause harm in a lifetime.

Unfortunately, clinicians don’t know which ones won’t cause harm and which ones will so we treat all cancers as if they will be harmful. This means that some cancers may be found and treated unnecessarily, leading to biopsies, surgery, potential infections, pain and can negatively affect quality of life. This is what is meant by overdiagnosis.

We want people to have the facts about the potential benefits, as well as harms such as overdiagnosis.

For breast cancer screening, if a someone 40-74 years wants a mammogram after being provided with the information on benefits and harms, they should be offered a mammogram every 2 to 3 years.

Clinician tools

Tools for discussing risk with patients